Jews in Poland: Between cultural-religious renewal and new uncertainties

Polish Jewry suffered the biggest losses of the European-Jewish population in the Shoah and experienced political (State Communist) pressure after 1945 in such a strong way that Jewish community (and cultural) life almost collapsed until the late 1960s. Only after the end of Communist dictatorship and the peaceful transformation into a Western-oriented society could start a certain re-construction of local Jewish life, mainly limited to communities in Warsaw, Krakow, and Wroclaw. The contemporary Polish Jewish community is estimated to have between 10,000 and 20,000 members.

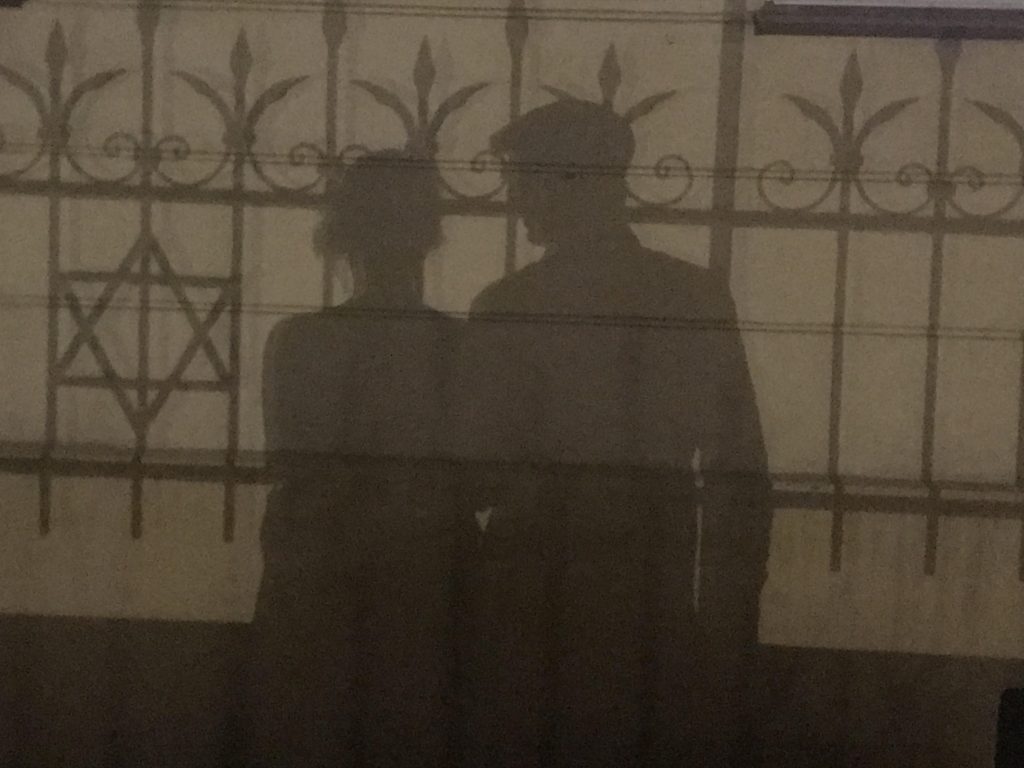

Poland has undergone very dynamic social and political transformations in recent years. At least some of them have affected Jewish life in the country as well – on the one hand, very controversial discourse on resistance, collaboration, and complicity under Nazi German occupation from 1939-44, strong trends of new nationalism, and especially the “Holocaust Law” in 2018; on the other hand solid and encouraging messages from politics and authorities acknowledging the Jewish legacy (huge program for restoring Jewish cemeteries, Jewish Museum Polin, Warsaw Ghetto Museum under construction, etc.) Thus, it was to expect that our interview partners would also talk about perceived ambivalences between a state policy, officially offering a lot of support in politics and culture for commemorating the Shoah; but also strong trends of historical revisionism, antisemitism (also from the religious side) and remarkable disturbances in the relations between Poland and Israel.

Like our interview series in Germany, we contacted a sample of Jewish and non-Jewish interview partners who are quite present in public, share responsibilities, and are willing to help shape public discourse on Jewish/non-Jewish relations in the past and present. We focussed on the question(s) to what extent Jewish/non-Jewish relations have significantly changed after the end of communism and to what extent a rapprochement is possible for re-working the shared past. We have also asked – as kinds of key questions – to what extent Jews in Poland feel accepted and integrated into non-Jewish majority society today; what they consider as core elements of their Jewish identity today; the meaning of Israel for their lives as Jews, and also their handling with new trends of nationalism and antisemitism in Poland.

As expected, some Jewish interview partners referred to the relatively small size of the Jewish communities, other Jewish institutions, and networks. Though, since at least our Jewish sample was very heterogeneous (including quite different age groups and people with quite distinct world views), we received significantly different answers regarding the future perspectives of Jewish life in Poland. Interestingly, some of the most active Jewish leaders offered a more or less sober view and did not join the “revival euphoria” presented in some media but confirmed Ruth Ellen Gruber’s thesis of a rather “virtual Jewish life” currently present in Eastern Europe (Gruber, 2002). However, the new and strong public interest by non-Jews in local Jewish history, architecture, Yiddish music and theatre, and more is not basically criticized and – to a certain extent – accepted as an attempt to re-establish or even to remake Christian-Jewish relations on the ground. Though expectations regarding opportunities, social effects, and possible “fruits” of an enlarged Christian-Jewish dialogue, expectations are significantly lower, for example, with those statements we’ve got from Germany.

This might be rooted, at least partly, in much more uncertainties caused by statements of Catholic representatives in public, sometimes repeating old anti-Jewish stereotypes typically for centuries. Some of our Jewish interview partners referred to quite different opinions and streamlines inside the Catholic Church, remaining hopeful for more constructive future dialogue.

Our Jewish interviewees mentioned an atmosphere of departure in some synagogues, projects, and Jewish interest groups, especially in Warsaw – though not typically for the general community (and maybe due to internationality, including Israelis living in the Polish capital). They also reported strong inner Jewish commitment, despite the difficulties of reaching the younger generation. “We have to compete with lots of alternative offers aiming to our Jewish youth, especially in the cultural scene,” told us one of the leading Jewish representatives in Warsaw. According to some Jewish interviewees, a certain number of young Polish Jews become very religious and observant, but then, in the next step of their development, they turned to Israel or the United States (often after marriage with a religious partner coming from these countries).

Similar to interviews with Jewish representatives in other countries under focus, we often heard that the ties to Israel are strong and that Israel remains important for individual and collective identities. Again, the number of Polish Jews opting for Alija appears rather low.

According to our interview partners, Jews in Poland feel accepted but not necessarily an integral part of Polish society. One of our interviewees said that, for example, Jews being in (Jewish-Christian) intermarriage could easily face some prejudice due to a widespread consensus that “Polish is just Catholic.”

Left-liberal Jewish intellectuals also expressed a certain discomfort when talking about actual political trends in the country (though they did the same when talking about the political trends in Israel). Religious interview partners were less critical and emphasized appreciation for government and state, especially regarding care for Jewish history preservation.

Most of our non-Jewish interview partners have been strongly driven by a commitment to civic society, preserving the history of minorities, Holocaust commemoration – and by activities against new trends of historical revisionism, also taking the risk of getting hostile reactions.

Some referred to former internships and voluntary work in memorial places (Auschwitz and others), which became key moments for their future life and thinking.

Conclusions

From our interviews with Jewish partners, we’ve learned that the Polish Jewish community is very active, committed, and vibrant, especially in Warsaw, Krakow, and Wroclaw. Though, future expectations are not too optimistic due to trends of aging and secularization (especially among the young generation). A growing interest of non-Jews in Jewish history, culture, and tradition is perceived and accepted, though not seen as causing substantial impacts on the Christian-Jewish relations “on the ground.” Jewish-Christian dialogue is practiced at some places, but it seems less than in other countries. Joint projects and efforts to explore Jewish history and preserve Jewish legacy are remarkable, thanks to strong initiatives by young non-Jewish Poles. Liberal intellectuals and a part of the Jewish communities expressed uncertainties by the new trends of Polish nationalism (in public) and the “Holocaust Law” in 2018 (only partly amended).